THE RESIDENTIAL AREA of Moholt in Trondheim is fairly typical for its age. It was planned and built in the 1960s and features three-story buildings with a centre stairwell and a brick façade. Today it is home to around 2,000 people, most of them students at Trondheim University. Now the first residents are moving into Moholt’s new student quarter: 632 new apartments, spread across five buildings, plus a preschool with capacity for 160 children. All made using crosslam. The developer is Trondheim’s Student Welfare Organisation. The project began with a competition in 2013, which was won by the Norwegian architectural practice MDH. As well as providing more housing, the new buildings are key to the regeneration of the whole area, according to Minna Riska, the partner at MDH responsible for the project.

“Moholt had some perfectly good brick buildings and a park-like landscape, but it had neither a hierarchy nor a centre. Our project creates a new heart in the existing student village, a public place with new housing, a preschool, a library and retail space in the geographical centre of Moholt.

“Our project also provided the architecture to meet the client’s demand for rational implementation and resource efficiency. At the same time, we were able to preserve the existing built environment and its structure by building on top of a large car park in the middle of the area. This gives us a clear distinction between old and new.”

Almost 6,500 tonnes of wood will be used to build the five nine-storey blocks in the new centre of Moholt. Widely held to be Europe’s biggest crosslam project, the development has attracted a great deal of coverage in the Norwegian media.

“And we expect even more as we near completion!”

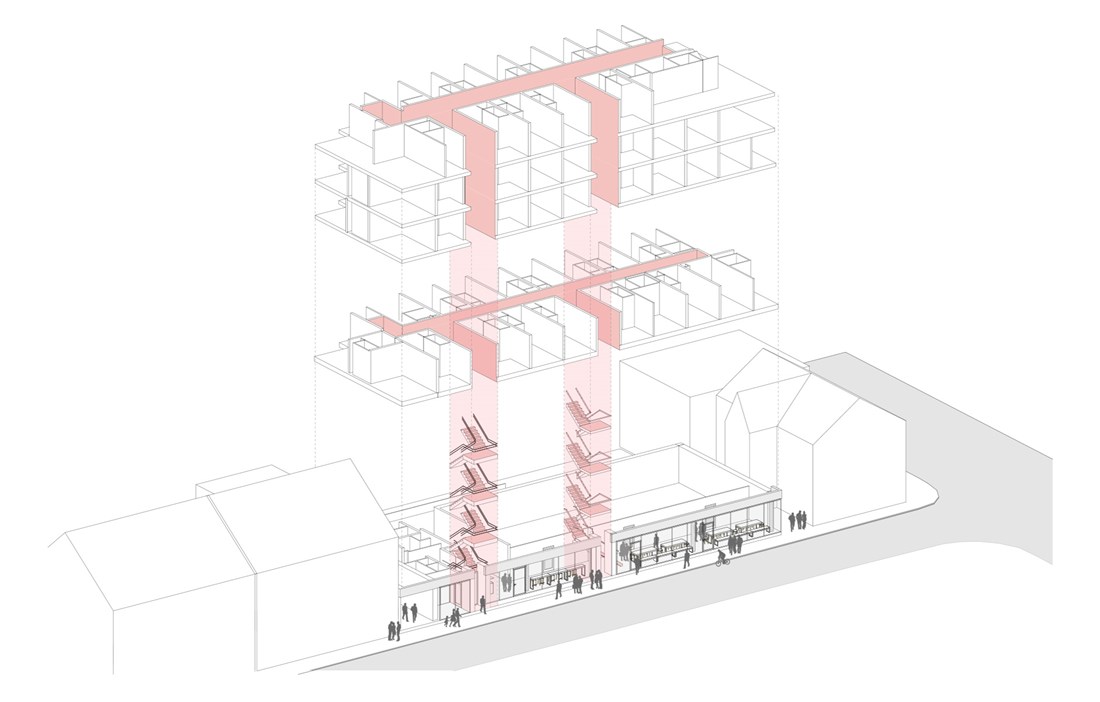

BUT MOHOLT IS NOT Norway’s only new student housing project where wood has played a central role. Five hundred kilometres south lies the small town of Haugesund. Autumn 2015 saw the opening of an apartment block here, squeezed onto a previously unused plot at Sørhauggate 100 that is just a short walk from the local university. The Haugesund block, also built in crosslam, offers space for around 90 students in small apartments. The ground floor has a large open space with a café and a cinema for the residents. The building was designed by the architectural firm Helen & Hard, which has offices in Stavanger and Oslo. The firm became aware of the qualities of wood when they were commissioned to restore a number of traditional buildings in the centre of Stavanger.

“We quickly saw how simple and ingenious traditional, wood-based construction methods are, the way they tolerate both use and change over time, but also their structural qualities. When we began working on new buildings, it felt natural to continue using wood as a construction material, not least because of its unparalleled environmental properties,” states Karen Jansen, one of the people who worked on the project.

Helen & Hard have tried many different methods of building in wood, relates Karen: everything from a pavilion with beams made from naturally crooked trunks to prefabricated structural elements. Like the blocks in Moholt, the student accommodation on Sørhauggate is built entirely in wood, from the lift shaft to the exterior façade. It was a condition laid down by the client and, again like in Moholt, it was constructed in collaboration with Itre, a network of Norwegian companies that works to promote wood construction.

“The relatively small and compact apartments, with short spans and slim recesses for the windows, made wood the perfect choice!”

THE BLOCKS IN MOHOLT, on the other hand, were initially meant to be built in concrete, steel and red brick.

“The competition had no material specifications. We based our entry on what we thought was the cheapest way to achieve quality student accommodation and what fitted into the setting.”

After the competition, the client had a rethink and was inspired to build student apartments in crosslam.

“We investigated whether our project was suitable for crosslam and it turned out that it absolutely was, so we proceeded on that basis. The advantages of low carbon emissions and a rational construction process were the main reasons for completing the project with cross-laminated timber for the structural frame.”

Student accommodation is based on the repetition of a large number of identical housing modules. This made it possible to fully exploit the potential for mass production and assembly on site as the units are delivered.

“In terms of price, it was better for the client, because of the excellent scope to employ various economies of scale.”

The size of the construction project in Moholt allowed for more economies of scale, points out Minna Riska.

Most of the inner walls have an exposed wooden finish, which also brought benefits, since it removed the need for plaster, filler and paint.

“As an architect, it has been rewarding to get to work with a construction material whose surface we can leave untouched, without any need for finishing! In addition, it enables us to develop ‘honest’ details – details that are effective in building terms but that also show the structure.”

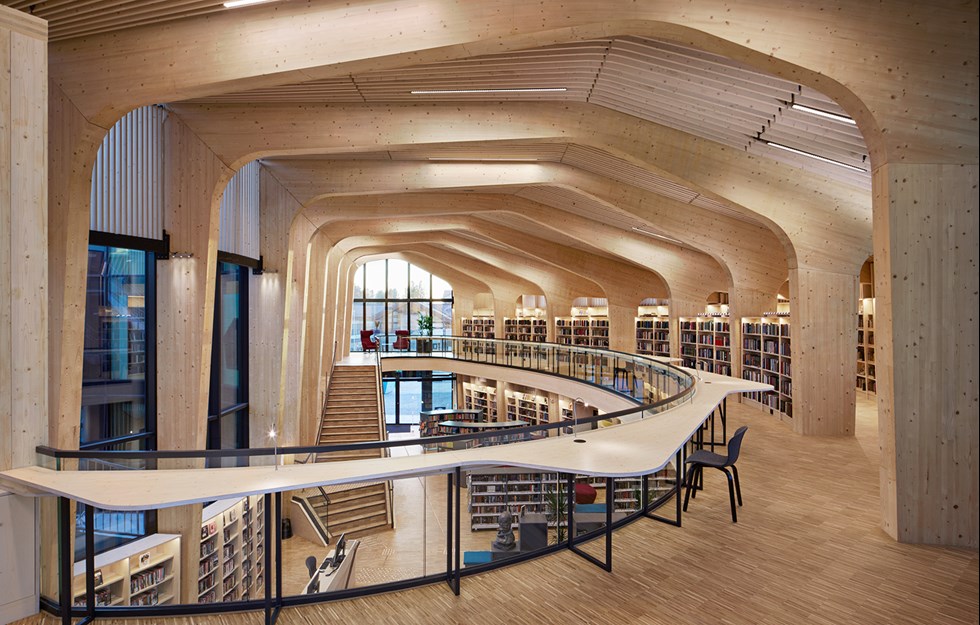

The residents on Sørhauggate will also have the wood as a tangible part of their living environment, explains Karen Jansen:

“We expose the wood as much as possible. Not least because it gives a visual and tactile quality.”

ANOTHER THING THAT UNITES the two construction projects is that they meet the Passive House standard. Minna Riska sees crosslam as particularly well suited to Passive Houses.

“This is partly due to the simplicity of the joins and transitions. Thermal bridges are not formed in the same way as steel and concrete.

“One of the disadvantages of crosslam, on the other hand, is that it provides less insulation against low-frequency sound. To meet the Norwegian requirements concerning decibel levels between different functions and housing units, we have used plaster or plywood insulation in some places. In principle, it would be possible to simply increase the thickness of the crosslam, but the cost of that could not be justified.”

The crosslam for the five blocks in Moholt was manufactured in Austria. This is because there is simply no production line in Norway that is currently able to handle the enormous volumes. Despite the transport involved, construction firm Veidekke estimates that the carbon emissions are 70 percent lower than they would have been if the apartment blocks had been built in concrete. The vertical, overlapping boards on the façades are, however, Kebony – an eco-friendly modified pine manufactured in Norway. The pressure treating gives the wood a dark brown colour. The building on Sørhauggate also has a façade of vertical cladding overlooking the street – but in this case using narrow pine boards given the Royal treatment, a technique developed by Moelven that is claimed to prevent the wood from greying for five to seven years.

“There is currently huge interest in wooden architecture in Norway,” says Minna Riska. “I believe this is because of the strong ties to our building tradition and the perceived opportunities for international marketing. But for inspiration we look to Switzerland and Austria, countries that are much further advanced when it comes to architecture that uses solid wood components!”

Text Mårten Janson