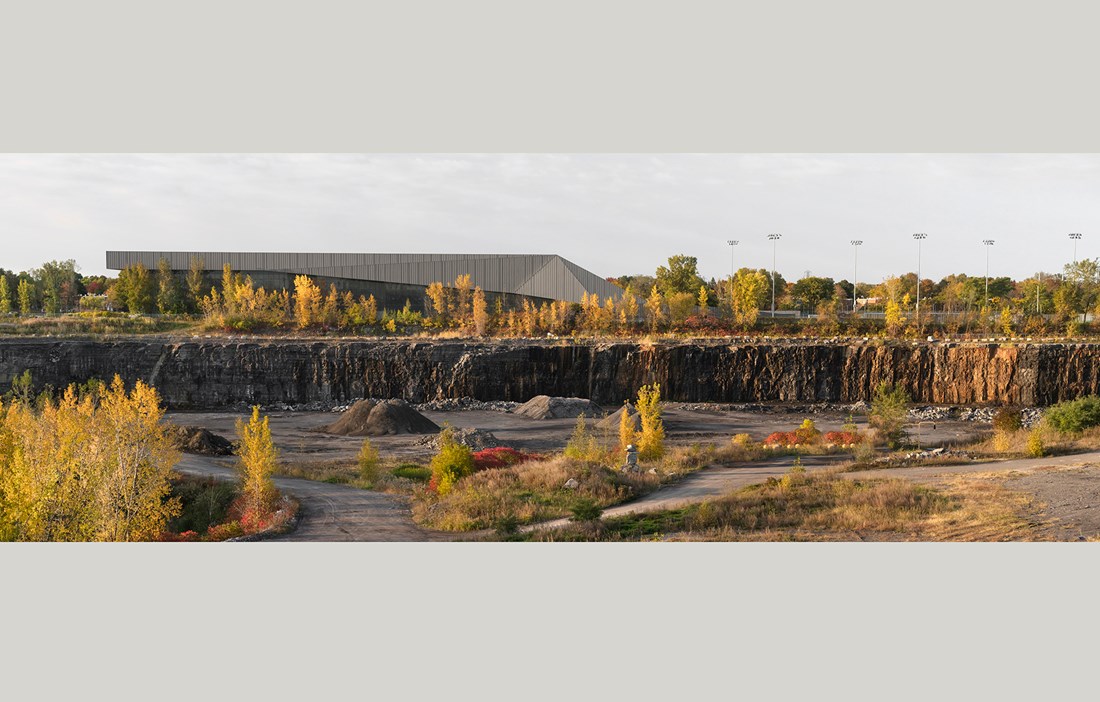

FIRST IT WAS a quarry, then a landfill site. Fast forward a few years and the land had become largely forgotten. Today the area in Saint-Michel outside Montreal is undergoing major changes – changes that will transform the place into a large and leafy park with lakes and paths. The city’s mayor has described the project as “a monument to sustainability” and many sections of the park are expected to be open in time for Montreal’s 375th anniversary in two years’ time.

The first thing to be completed in the new park is the football stadium Stade de Soccer. The shimmering matt grey colossus spreads out along the west end of the park and, after just a few months in position, it already feels like a natural part of the landscape. The architectural practice Saucier + Perrotte won the competition in no small part due to their ability to seamlessly merge the building with its surroundings.

“We used a limited range of materials in the project to maintain the sense of being close to nature. The entire Stade de Soccer de Montréal is poetry in motion. The indoor and outdoor football pitches form an attractive ensemble,” says Gilles Saucier, the chief architect at Saucier + Perrotte.

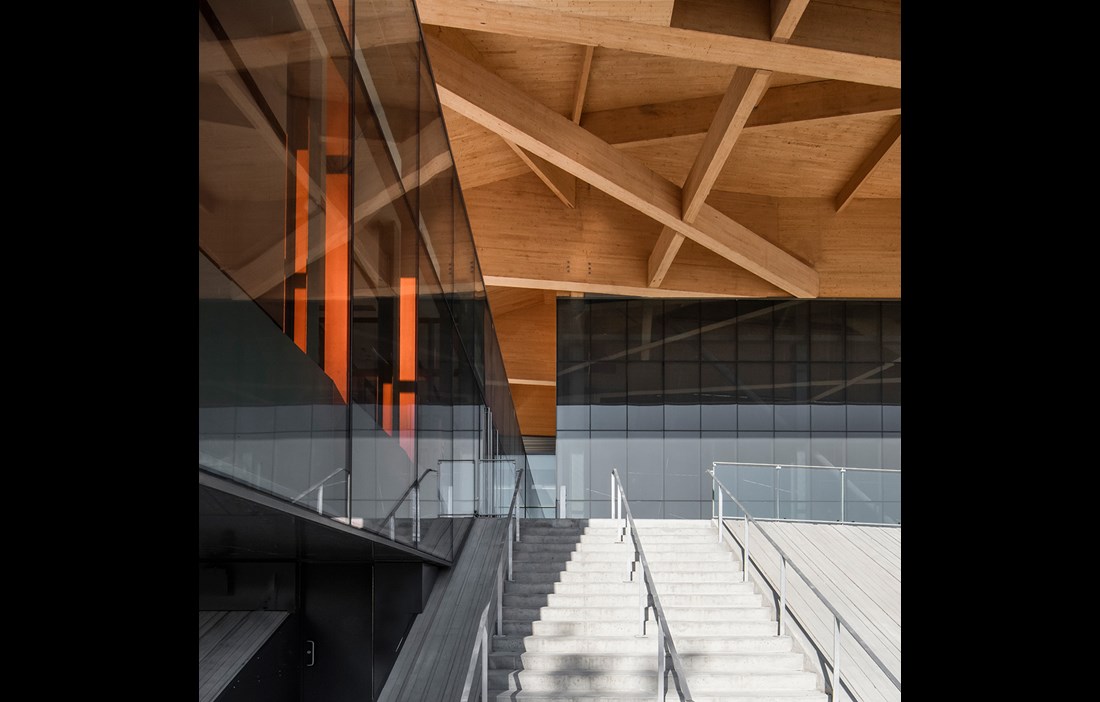

THE ROOF SWEEPS DOWNWARDS on one side, spreading out into two “arms” that embrace the outdoor pitches. These open up further towards the city, forming a gateway between Montreal and the park. Corridors on two levels run along one side of the indoor pitch. From the entrance, the lower corridor leads to the changing rooms and toilets, while the upper corridor leads straight out to the spectator seating for the outdoor pitches. One arm of the building thus forms a grandstand.

The limestone that was once quarried here was used to build large parts of the city. It was therefore only natural for the football stadium to reflect this industrial past. Adjacent to the building stand sharp, vertical rockfaces left over from the blasting, and it was these lines and colours that informed Saucier’s design.

“We were very much inspired by the old quarry, which has left plenty of traces behind. I wanted the building to look like a block of limestone rising up out of the ground. The roof and façades are clad in zinc, which reinforces the overall look. The project is a representation of the material that once built Montreal,” comments Saucier.

While the exterior is an expression of hard, dark minerals, the interior has a much softer feel. The football pitches are dominated by the gigantic wooden roof structure. The 13 main beams, which are 69 metres long and weigh 77 tonnes each, were developed in close collaboration with Nordic Structures. They were manufactured in Quebec and due to transport restrictions they were delivered in 23 metre lengths that were then rigidly joined together on site. The result is an impressive display of what wood can do.

“As an architect, this type of building can be hard to put any really distinctive mark on. It felt like the roof was one of the few places where we could do something different. Wood was an obvious choice, because it is a material that speaks for itself so eloquently, plus wood is practically in our DNA here in Canada. But we wanted to go a little further. We wanted to show the world how wood could be used in large and unusual structures.”

THE STRUCTURE GAINS ITS STRENGTH from two engineered wood products – glulam and crosslam. The top and bottom of the beams is made from glulam and the rest is crosslam. The result is a wooden structure that is relatively light, cost-effective and strong.

“This is something truly unique. Never before has a crosslam structure with such a large span been built anywhere in the world. One of the challenges for us as engineers was to develop special screws to hold together the three parts of the beams, which are subjected to force of up to 10,000 kN (over 1,000 tonnes, ed),” explains Jean-Marc Dubois, project manager at Nordic Structures.

ONCE THE BEAMS had been put together, they were hoisted up by three large cranes and manoeuvred into place. This was a special moment and a milestone in the long and arduous task of creating a sustainable and innovative building – the only one of its kind. For Nordic Structures and Saucier + Perrotte, the project was a dream come true.

“Saucier + Perrotte are visionaries and it was an honour to work with them. In rising to the project’s challenges and the high expectations from the architects, we managed to deliver a solution that would hardly have been imaginable five years ago,” says Jean-Marc Dubois.

Combining glulam and crosslam created a very strong hybrid that can handle the forces to which the long beams are exposed. The fact that the beams are hollow means that they are lighter, and that various installations can be concealed inside. The use of solid beams was not an option, as it would have been too expensive. Wooden beams were also a good choice in terms of the sustainability drive that runs through the entire project.

“Travelling far and wide to find large enough trees for our massive roof was out of step with the project’s guidelines on sustainability. Instead, the beams are made 90 percent from small wooden blocks, 50 millimetres by 100 millimetres, from short black spruce trees grown not far from Montreal. I find it kind of beautiful that we were able to use trees no-one else would bother with,” says Gilles Saucier.

Looking up at the roof on the inside, the first impression is that the beams have been positioned rather haphazardly, without any real system. That is precisely the look that Saucier + Perrotte wanted to achieve.

“One of our goals was to get away from the feeling of a sports hall and instead give the project a warm, scaled-down feel. That’s why we used wood, and it’s also why we designed a roof that looks almost random, to make visitors forget that they’re looking at roof trusses. However, there is in fact nothing random about the roof. On the contrary. The beams are closer together in some places because of a need for reinforcement in that particular spot,” says Saucier.

The huge roof structure cannot fail to attract the gaze of visitors, but it is not the only part of the project that involved planning on a large scale. When it came to laying the large artificial grass pitches, meticulous work was required to create a level cement foundation that also closed off any gas leaks from the time when the site was used for landfill.

“It was a fantastic sight to watch the machines working on levelling out the concrete. They were a serious piece of kit, but they were dwarfed by the building. The enormous field of cement made them look like little toy cars,” continues Saucier.

Since the stadium is so huge, the architects worked on various details to bring it down to a more human scale. It was important that as well as feeling like a huge colossus, it was also warm and inviting. Much of the vegetation around the stadium was preserved and additional trees have been planted around the site. Over time, the building should look like a rocky mound rising up out of the forest. Large areas of glass have also been used to create a sense of openness.

IN THE AFTERNOONS AND ON WEEKENDS, the stadium is full of football players. Gilles Saucier says that he sometimes goes there on Sundays to watch football matches. He has particularly noticed how many young people become excited when they enter the stadium and look around the vast space in wonder.

“They tend to run around and pretend they’re famous football players. They do goal celebrations, shout and pretend they’re being watched by a huge audience. It’s fantastic to see how the splendour of the building can have this effect on them. That it can transport people to a different place, a different reality. The Stade de Soccer project makes them stars,” says Saucier.

Text Erik Bredhe