STANDING AT THE top of the winding wooden staircase, staring down at the floor far below, a film title pops into my head – Vertigo. In Hitchcock’s 1950s classic, former policeman Scottie shadows a woman who insists on visiting places at high altitude. His fear of heights makes this a problem for him.

At Ulls Hus – the new main building at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU) – students slip up and down the impressive staircase. Others stand with a cup of coffee or chat on the staircase’s small landings, which are positioned between the six floors. The beautifully untreated handrail feels warm to the touch and gives off a lovely scent of spruce. The stairs dominate the interior of the entrance building, known as Kuben or the Cube, and immediately capture the attention as you walk in. However, wood is not just reserved for the stairs – the material appears in the façade, the walls and not least in the exposed wooden structural frame.

“From day one, we knew we wanted to do this building in wood. And we wanted the wood to be seen,” explains Paul Kvanta, chief architect at Ahrbom & Partner.

PAUL KVANTA AND HIS COLLEAGUES suggested wood because it expresses the mix of Swedish agricultural tradition and modern research that defines SLU. The visible frame, for example, is reminiscent of old barns and storage sheds.

But to find modern references for buildings with a visible wooden structure, they turned primarily to foreign designs. The UK, Austria, Germany and Switzerland have fine examples of the type of building that Paul Kvanta and his colleagues wanted to create. Visible carcasses of cross laminated wood (CLT) are rarely used in Sweden today, and particularly not for large statement pieces like a university building. This initially put the project on shaky ground. Would SLU and the actual client Akademiska Hus dare to go all the way with solid wood or did they want steel and concrete? For a few tense autumn weeks in 2011, Ahrbom & Partner and the structural engineers at Bjerking drew up detailed drawings for one version in concrete and one in wood. In the end, the project became a compromise. The large entrance building Kuben, with its six floors, was kept in wood, while the rest of Ulls Hus – Klustret and Ryggen – would be built around a steel and concrete frame. However, they too were given attractive wooden façades of silicon-treated, radially sawn heartwood pine in the inner courtyard.

“Everyone involved was really excited when we finally got going. And chief structural engineer Björn Johansson at Bjerking who we worked with was incredibly enthusiastic when we said we wanted a visible structural frame in wood for Kuben! He has extensive experience of wooden carcasses, but he longed to build something where the wood truly had the starring role.”

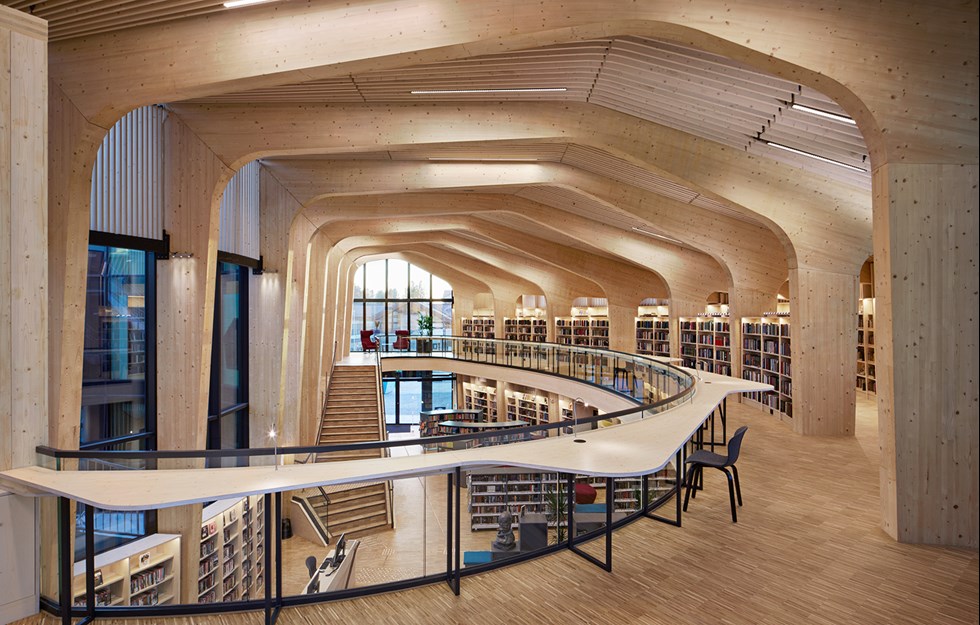

KUBEN IS BUILT UP around a frame of glulam pillars, and when you go into the main entrance, you are struck by the 1000 m2 ceiling, comprising a CLT structure supported by a network of glulam beams. Between these, sound absorbers are suspended for improved acoustics. To keep the whole ceiling visible and to emphasise that the entrance hall is one single room, all the dividing walls are glazed.

The architects had the idea that everything in Kuben would be arranged in a modular system. Everything is thus built around the glulam pillars, which are spaced 7200 mm apart at the centre, subdivided into spaces of 2400 mm. The stone flooring is 600 x 600 mm, and the glazed sections are 1200 mm. And so on. The only elements that are allowed to break this modular approach are the staircase and the lift shaft. The intention of this strict system is to create a calm and harmonious, and at the same time monumental, environment that lives up to its role as the main entrance to one of the country’s leading universities.

“We felt a little like architects of old as we drew up our modular system. But getting the Swedish construction industry on side with a project like this is not usually the easiest of things. It demands a great deal of work on getting everyone on board, and we have to be on site to help out and make sure everything is right.”

Paul Kvanta explains that you usually have to fight to be involved in the actual construction process, but here the client Akademiska Hus and the contractor Peab valued their involvement.

“I think that was brilliant. Without the excellent collaboration and consensus between us architects, the developer, the tenant and the builders, the result would never have been anywhere near as good.”

At six storeys, Kuben towers two floors above the rest of the area. Its three lower floors house the entrance lobby and are fully glazed onto the outside world. The three top floors contain offices, meeting rooms and reception rooms for SLU’s administration and management. The façade is lined with black-painted, radially sawn cladding in heartwood spruce. Using radially sawn wood avoids the timber splitting and bowing, which is particularly important in this case, since the black paint contributes to greater temperature differences.

THE CEILING IS TREATED WITH a matte wood varnish with UV protection to prevent yellowing. Before that, it was sprayed with a clear flame retardant lacquer to protect against fire. The team spent a great deal of time finding a flame retardant that both works well and looks good. Most of them gave a shiny and runny end result, and that would have made the wooden building look very different.

“I spent a whole evening googling flame retardants. Suddenly I came across the concert hall in Kristiansand in Norway. It turned out the Norwegian state had laboured for a year to develop a smart and effective flame retardant for the project – and they succeeded in the end! I emailed the guy at the company Eld och Vatten and received an answer that same evening. He was over the moon that I wanted to use it. And we were equally pleased!”

One major challenge was to achieve good sound in a wooden structure, or rather to reduce sound levels. The architects and structural engineer sought the help of acoustics expert Lennart Karlén from consultants ACAD, who worked on the Stockholm Concert Hall, amongst other projects. And the sound damping really shows.

Walking up the stairs, I see a man on his way down. “How lovely that he’s walking around in his socks here at the university,” I get to thinking before I meet him and see that he’s wearing perfectly ordinary men’s shoes.

“Achieving good acoustics is incredibly important. All the sound damping measures have been incorporated into the top of the floor structure. So if there is a corridor above a large meeting room, for example, a person should be able to walk along the corridor in heels without the people below hearing a thing,” relates Paul Kvanta.

Having a building like Ulls Hus gave a real lift to the whole institution. Everyone used to be spread out in small buildings, relatively isolated from each other. But the new building encourages students, lecturers and administrative staff to meet spontaneously and enjoyable, creative interactions to occur.

“People who were previously just a signature on a piece of paper to each other can suddenly come across each other in a corridor. The building has become exactly the social meeting place we were hoping for. And it’s a great feeling when you hear that people are using your building precisely as you had hoped,” Paul concludes.

TEXT: Erik Bredhe