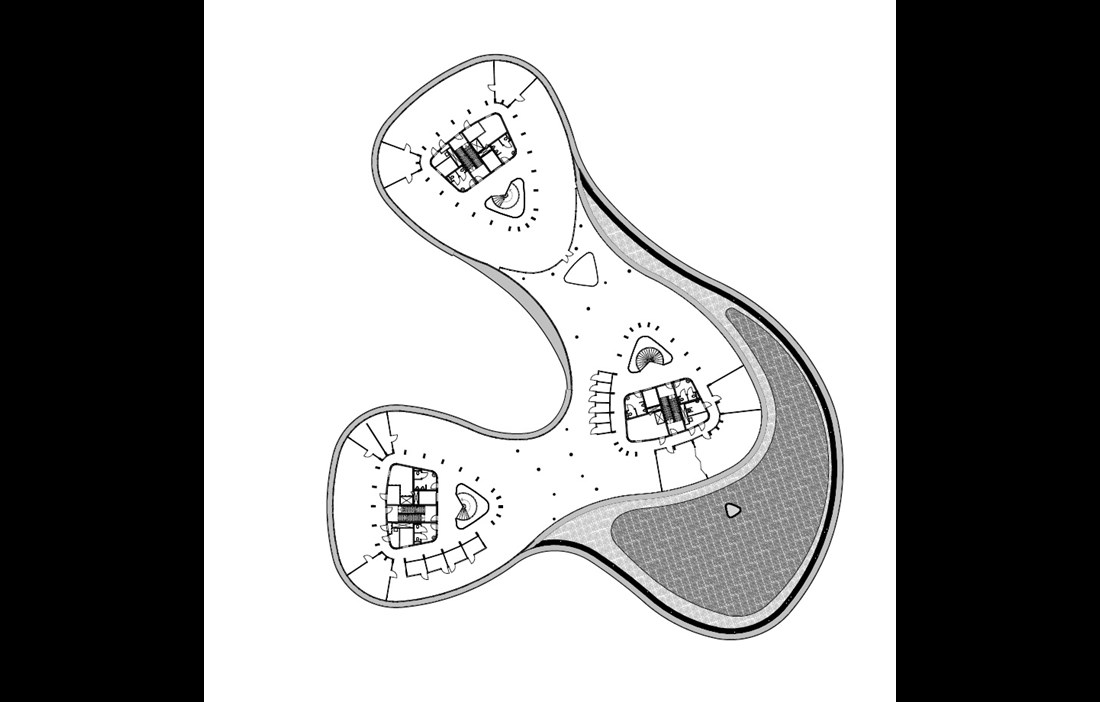

The bank’s new offices are attractively situated on the verdant De Reehorst Estate in Zeist, 12 minutes by train from the fourth-largest Dutch city of Utrecht. Viewed from above, the building is a little like an elongated three-leaf clover. Standing just a few metres away, the billowing movement of the forest follows the form of the building. But it wasn’t the forest that had to give way to the building, but vice versa.

»We had a report showing the paths that the bats were flying, and we didn’t want to get in the way of that. So we designed the building in a way that would keep us 10 metres from the existing trees,« explains Erik Mulder, who was responsible for the project, along with Thomas Rau at RAU Architects.

It was also no coincidence that the new bank headquarters ended up where they did from a broader geographical perspective. It was around here that the bank first launched its business 40 years ago.

»We had grown out of our old premises and were looking to relocate. In contrast to our previous offices, we had a non-negotiable requirement that the new site would be near a train station. And that the building would be an expression of our identity. But when we looked, we couldn’t find a suitable option right next to any of the more central cities, such as Utrecht or Amersfoort,« says Matthijs Bierman, former CEO of Triodos Bank in the Netherlands, who was deeply involved in the construction of the new offices.

Triodos Bank has an explicit sustainability profile, with all investments having to meet good standards of economic, ecological and social sustainability. When the bank began planning the new offices in 2011, they naturally also wanted their own headquarters to be at the cutting edge of sustainable building. To work out exactly what that might mean, several workshops were held jointly with the architect, landscape architect, interior architect and other consultants.

»As the plans began to take shape, Thomas Rau also put forward the idea that the building should be entirely circular, and the bank was brave enough to go with it,« says Erik Mulder.

In addition, the decision was made early on to build in wood.

»It was Triodos that decided the load-bearing structure should be made entirely from wood, which is quite unique for a building of this type. But it also feels like a completely logical decision in view of the focus on sustainability and circularity that this project has,« adds Sander Kok, project manager at structural engineers JP van Eesteren.

This means that absolutely all of the materials in the building, except for the concrete foundations, can be disassembled and reused in new contexts. And using wood for the frame made this possible.

»The only exception to the wood is that we’ve inserted narrow steel posts between the glazed units in the façade to avoid the floor bowing when people walk along the inside of the windows. The steel posts also channel water down from the roof,« says Erik Mulder.

In addition, the design avoids all types of elastic sealants and only uses metal screws – 162,382 of them – that can easily be removed.

All the materials used in the building are carefully documented, including their grade and specifications from the suppliers, and where in the building the material can be found.

»We work in 3D and build up the entire structure on the computer, and it’s here that we link in information about each individual element. Thomas Rau has created a platform for this, with different identity numbers that mean we can see exactly what we could recover from the building and use again,« explains Erik Mulder.

The materials have also been registered in the material bank Madaster, a new public service where property owners can register material assets in their properties.

»Triodos’ new offices are the first in the world to do this on such a grand scale. As such, the new building is not just the home of a financial bank, but also a material bank,« states Erik.

Prompting Madaster and the thinking behind it is the realisation that the world’s raw materials and material resources are finite. As the supply of different materials shrinks and prices rise, it will become not only financially viable to reuse materials this way, but also a necessity in order to make the planet’s resources stretch.

»At this moment in time, the material with the greatest financial value in the building is copper. But when the time comes to recover the materials, many years down the line, this may well have changed. And in terms of resources, there may be a greater shortage of some types of material that are currently readily available – such as wood, which is becoming increasingly expensive. It is therefore well worth recording all the materials in the building,« adds Erik Mulder.

A key factor in establishing the circularity and wider sustainability of the building was the use of wood for the load-bearing structure.

» IF SOMEONE WANTS TO TAKE DOWN THE WHOLE BUILDING IN 20 YEARS, THAT CAN BE DONE QUITE EASILY.«

The building is essentially three towers of different heights, which are linked together by a shared ground floor. The unique load-bearing structure on each level of the towers is like a mushroom, with a stem and a cap with gills on the underside. This also makes the wooden structure a core element of the visual identity. The design is a combination of glulam and CLT, made in the Netherlands using softwood from Germany.

»The mushroom-like structure in the middle is made of glulam. Running inside this is the section housing the stairwell, which is made of CLT along with the beams around the lifts, cloakrooms and toilets. The same is true of the floor system, which comprises 120 millimetre-thick CLT elements, cork flooring and several layers of sound insulation,« notes Erik Mulder.

In all, the design uses 1615 cubic metres of glulam and 1008 cubic metres of CLT. The restaurant also makes use of five natural tree trunks, which serve as both visual and load-bearing elements.

Many of the elements were able to be prefabricated and assembled in advance, including large parts of the ‘mushroom structure’, the CLT floor system and some of the panels.

»On that subject, one of the unique moments was the installation of the 16.5 metre-long wooden elements for the lift shaft, which we put in place with a single crane lift,« recalls Sander Kok.

The high degree of prefabrication meant that the construction time could be kept relatively short. »It meant we were able to erect three floors in just a few days and complete everything in a total of 13 months,« says Erik Mulder.

Wood also features in many other places around the building. The small service units on the roofs, for example, are clad in pine that has been acetylated to improve its durability and reduce maintenance. Some of the chairs in the building, along with the handrails for the fire escape stairs, are made of wood taken directly from the property itself. Taking into account all the fixed wooden installations, the building stores over 1633 tons of carbon dioxide, which is more than it emits – even including the production time.

»Another great fact is that the building already has several circular features. The wood flooring in the restaurant is recycled, as are the wooden beams in the ceiling, which come from an office in Rotterdam,« says Erik Mulder.

Although the façade is almost entirely glazed, the building has good acoustics. This is in part due to its soft, rounded form, which prevents the sound from bouncing directly off the hard glass, but also the good sound insulation properties of the floor and wall systems. In addition, the ceilings in some of the spaces are fitted with a perforated acoustic screen in metal.

»Plus, the office areas are fully carpeted for further sound reduction. To ensure that the carpets are easy to take up at a later stage, they have been secured in place with double-sided tape,« adds Erik.

Alongside the circular efforts, several other measures have been taken to help make the building one of the most sustainable office blocks in the world. One of these is the facility’s 3,000 square metres of solar panels that are fitted to the roof over the car park. Together, they produce around 505,000 kilowatt hours a year, which is more energy than the building consumes. With the help of a smart, bidirectional charging system, the electric cars connected to the system can be used for temporary storage of energy that is surplus to the building’s requirements.

The green sedum roofs on the towers fulfil several functions. One is that they collect water that is then channelled away and used to flush the toilets. Another is that they support local insects and birds.

»The restaurant roof, which is slightly larger, also has some larger plants to improve biodiversity by attracting different types of birds and insects,« says Erik Mulder.

Last but not least, the building is designed to uphold and promote human values. Each floor has natural meeting places where colleagues can get together. In the areas between the towers there are open spaces where you can sit and talk, as well as meeting rooms and workrooms of different sizes. The ground floor, which houses the restaurant, is also open to external visitors.

The glazed façade is surrounded by nature, offering great views and plenty of natural daylight. However, there is considerable flexibility. If you don’t want daylight, you can simply screen it out, the temperature can be regulated everywhere and all the windows can be opened.

»There is no doubt this building is fully focused on people. There is a huge amount of choice, and working here should be both comfortable and healthy. Natural, non-toxic paints and materials – the main one being wood – contribute to a good environment,« comments Erik Mulder.

The thing he’s most pleased about regarding the whole project is the commitment from everyone involved, which has made it possible to pull all the elements together to create a successful whole.

»Our speciality at Rau is working on sustainable buildings. But this is by far the most circular one we’ve done so far. If someone comes along and wants to take down the whole building in 20 years and use the parts or relocate it somewhere else, that can be done quite easily, which makes me feel incredibly proud,» says Erik.

Sander Kok agrees: »I’m proud that we’ve had the courage to take this on and be the first in the Netherlands to realise a sustainable building in wood on this scale. We’ve learned so much along the way and helped to give the construction industry – and maybe the whole world – some forward momentum. I’d love to do more projects like this and put what we’ve learned to good use.«